The Image

Images are commodities broken and weaponized by a gluttonous corporate class. Why produce or traffic them?

Welcome to the inaugural dispatch of Studio Practice with Andy Gottschalk, a newsletter documenting the challenges and triumphs of maintaining a creative life.

To start this newsletter, I wanted to continue a tradition that I’ve rehearsed for several years on Instagram: sharing ten or so impactful books I read in the previous year by pithily recapping and reducing them in typo-laden blurbs.

Books are foundational guides to my creative life. I consider them friends to all arts because the best of them force us to reconsider our a priori assumptions about life.

But I want to save my yearly critical evaluations for the next dispatch. First, I want to focus on one idea I read about a lot this year, from a text that may have very well reordered my understanding of art.

The book is The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America by Daniel J. Boorstin. It’s remarkable for having coined the term “pseudo-event” to describe the contrived affairs reported by media (PR events, press conferences, photo ops, and the like). It gave a name to the undeniable primary mode of mass media today: the creation and maintenance of illusions.

Boorstin’s book shows a nation peculiarly committed to creating events for the sole purpose of being photographed and broadcast, events that, outside their media function, fail to provide any value or meaning to the public.

He soberly bemoans the media’s slavish dedication to surface-level images, entertainment, and trivia. With the rise of media technology capable of reaching greater distances and less immediately relevant audiences than ever, he paints a picture of extreme simulation, in which a reader or viewer effectively swims in imagery contrived for the sole purpose of lubricating consumer desire, advancing brand loyalties, and promoting feelings of friendliness with distant “public figures.”

Boorstin wrote The Image in 1962 as a prophecy.

I admit I came to The Image from first reading, nearly in one sitting, a late spiritual sibling of it called Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle, written in 2009 by the war reporter Chris Hedges.

Empire of Illusion is a deeply polemical book. It criticizes a media culture and pliant citizenry obsessed with trivia, stardom, influencers, body modification, abuse of women and with pornography, and a grotesque denial of the divine. It sees a citizenry increasingly divorced from reality by illiteracy, lack of faith, and excessive consumption.

Additionally, I read Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, which seeks to describe the precise propaganda filters that sieve stateside reporting into pro-U.S., pro-government pieces of journalism. They illustrate the disastrous consequences a dominant commercial media has in reporting (or not reporting) military and corporate abuses. Through relentless case studies, the book details the incentives that drive U.S. propaganda.

And most recently, to complete this little syllabus, I returned to the subject of images and their tricky penchant for entertaining or deluding by reading Neil Postman’s 1985 Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Far from serving as a reliable tool in informing, Postman argues, images in television over-index on their need to entertain and amuse, and create spectacles where serious debate and important issues used to reside.

He argues that in an (imperfect) formerly typographically-oriented society, the literate citizenry would read their news and know their public figures by their words. The citizenry had a remarkable recall of speeches, debates, and recitations.

Compare this to the past century, during which we have subsisted on soundbites and know figures mainly by their faces. We are familiar with mere icons, the products of teams of advisers, stylists, surgeons, and brand managers. The closest we ever get to typographic recall is the dreaded sloganeering we’re sold—on campaign trails, advertisements, and elsewhere.

In a demented twist, we confuse the ubiquity of a slogan or the catchiness of a sonic logo with the values of well-knownness. It’s well-known; thus, it becomes imperative to engage with it.

Of course, this type of image, the dominant media image, the one that shows off and has a jingle and a slogan and an extended cinematic universe and a quarterly earning and a subscriber count and a call-to-action and a price tag… this image is designed to deceive. It is not meant to inform. It is meant to supplant reality itself with something agreeably consumptive. It is anti-art.

The question all this poses to artists is one of saturation and ethics. In an environment drenched in human-made ideas and imagery (and increasingly corporate as well as increasingly synthetic, A.I. imagery), what is the value of being a person who makes images?

And the urgent question it posed for me when I began thinking about these issues was: what is the value of being a person who competes to have their images seen?

I grew increasingly distrustful of slick engagement, of likes, of the super-egöic need to make artwork that spoke to present concerns and attitudes informed by the cultural thuggery of social media and its Pavlovian dictates. The bitter cocktail of appearing moral yet ironic yet inventive resulted in empty signposts and too much overthinking for a small online audience of people fractionally engaged with what I had to say. All this for a presentable portfolio so a gallerist/hiring manager/whoever could have the correct reaction to my work and commission/employ/congratulate me. The art of the art was gone.

The need for artistic approval has obvious risks, and the online wish-fulfillment of forming community and collaboration can pervert into something transactional.

Plus, there’s the question: how does someone even exhibit work today? Who is it for, and why, especially when the work is to be seen in a slew of other content, abutting relentless advertisements, product campaigns, and endless documentation of similar-looking artwork?

In this particular form of distribution—the artist as content creator—the art briefly serves a fractured and fleeting attention span, and hardly anything else. Cynically, it might be hoped that the art will land in a repository of images so that an intelligent robot can make something familiar but novel from it. More briefly seen imagery can come of it. It is degrading.

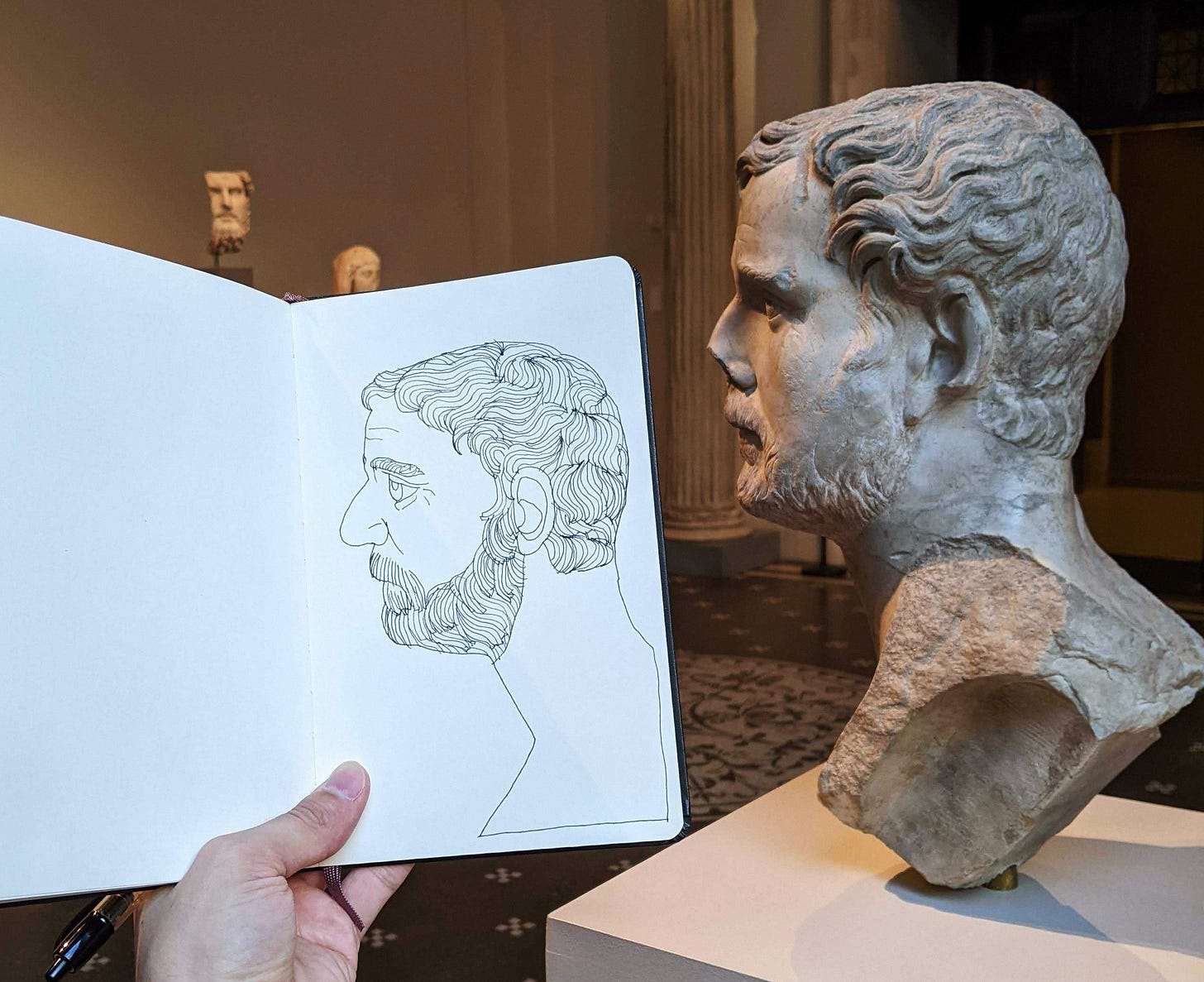

Yet I know there is value in making images. I love putting pencil to paper, I attend figure drawing classes. The slow observance I have always loved in looking at other people and capturing them holds its charm. Making images this way reaffirms what I care about in art: translating (or re-translating) the observable into something material.

As an image-maker with a private artistic life as well as employment on behalf of a well-mobilized (and hungry) corporate class, my interest in imagery and my understanding of art has been utterly reshaped this year by Boorstin’s ideas. I refuse to let them go.

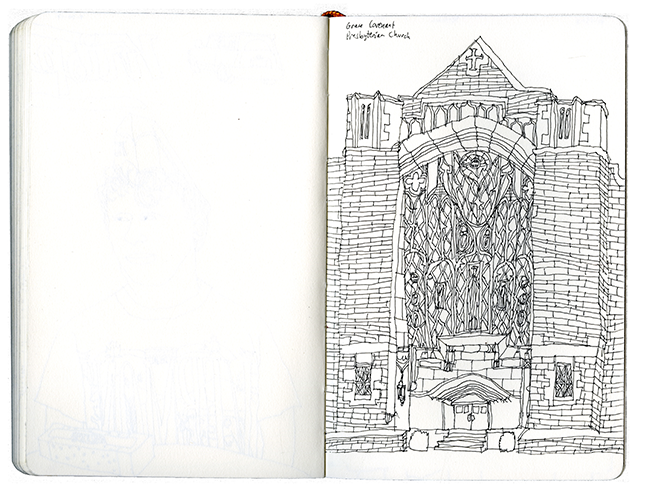

Since reconsidering the value of producing images, I've returned to an embrace of reading, of keeping a sketchbook, of writing little stories. I have largely refused social media, and have not missed it.

I’m reevaluating what a meaningful creative life looks like, especially considering I maintain my art practice alongside my friendships, relationship, family, job, and health.

I hope, in this newsletter, to share what I learn about making and maintaining a studio practice.

some real chewy food for thought! i've been leaning into the analogue lately, too, though i'm still shackled to social feeds by employment and a lust for those twin imps -- content, and fame. so i'm excited to vicariously explore life on the other side through your gottschalkian witticisms!